The case of Cardtronics UK Ltd and others (Respondents) v Sykes and others (Valuation Officers) (Appellants) [2020] UKSC 21 concerned the treatment for rating purposes of ATMs situated in supermarkets or shops. We have reported in these news pages on the various stages of this litigation. The appeal process began before the Valuation Tribunal for England (VTE), which determined that all the sites of the ATMs were rateable separately to their respective host stores. The ratepayers appealed against that decision to the Upper Tribunal (Lands Chamber) which determined that those ATM sites facing outside their respective host stores were separately rateable, because they could serve customers other than shoppers in the store. Both the ratepayers and the Valuation Officer appealed against this decision to the Court of Appeal, which determined that none of the ATM sites was separately rateable from their host stores, because the host stores had not parted with possession of the ATM sites and retained “general control” over those sites as part of the facilities provided by the stores.

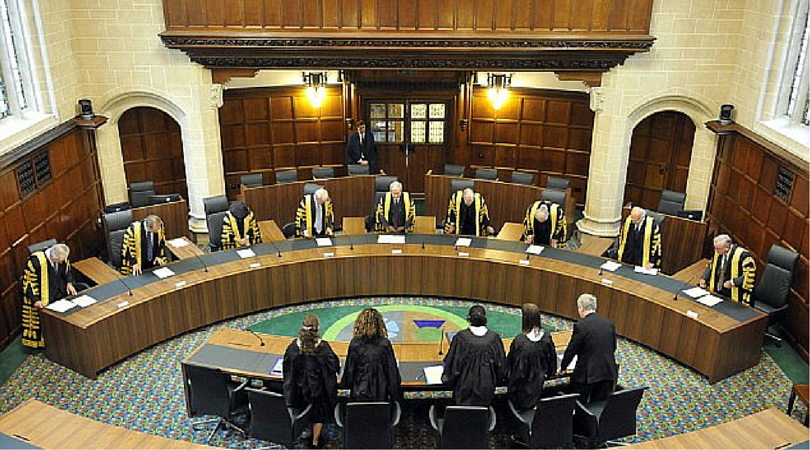

The Valuation Office Agency appealed to the Supreme Court against the Court of Appeal decision. The Supreme Court considered two main issues: first, were the sites of the ATMs properly identified as separate hereditaments from the stores or shops? Secondly, if so, who was in rateable occupation?

On the first issue, the Supreme Court reviewed the judgments of the Upper Tribunal (Lands Chamber) and the Court of Appeal, and accepted the reasoning expressed by the Upper Tribunal:

“We are therefore satisfied that each of the appeal sites, with the exception of the first floor site at Tesco’s Nottingham store (where the machine is free standing), is capable of being the subject of a separate entry in the rating list” (Para 151 of the UT (LC) decision).

In respect of the site of the “moveable” ATM, the Supreme Court found that the “essential qualities” of this ATM were “impermanence and mobility” and, accordingly, the Upper Tribunal and the Court of Appeal had been correct to determine that, in the light of these characteristics, its site could not form a hereditament. The sites of the remaining ATMs were, in principle, capable of being identified as separate hereditaments.

In respect of the second issue, the rateable occupation of the sites of the ATMs, the Supreme Court endorsed the finding that the retailers retained occupation of the ATM sites, accepting the reasoning of the Upper Tribunal:

“The Store has not, in any of these cases, parted with possession of the site of the ATM, but it has agreed to confer rights on the Bank which substantially restrict the Store’s use of that small part of its premises which comprises the ATM site. The Store has agreed to that restriction because the presence of the ATM furthers its own general business purposes and because the operation of the ATM by the Bank provides the Store with an income.”

The Supreme Court approved the finding of the Upper Tribunal that “Both parties derive a direct benefit from the use of the site for the same purpose and share the economic fruits of the specific activity for which the space is used.” The Supreme Court considered this was sufficient to support the conclusion that the sites of the internal ATMs remained in the occupation of the retailers and that the ATM sites did not, therefore, comprise separately rateable hereditaments.

The Supreme Court found there was no distinction between internal and external ATMs in this respect, and found that any difference between internal and external ATMs was not sufficient to alter the findings in respect of the internal machines. Accordingly, the Court considered the host store owners, and not the ATM operators, were in rateable occupation of all of the ATM sites, and dismissed the Valuation Officers’ appeals.

This judgment brings to an end more than six years of litigation on this subject. As well as being a relief to the ratepayers concerned, the decision also represents a victory for common sense and practicality in the rating system. Had the Valuation Officers’ arguments succeeded there was the real prospect that the number of rateable properties (hereditaments) in England and Wales would have expanded massively. By way of example, a corners shop, currently forming a single hereditament, could have become three or more separate hereditaments – a shop, a lottery terminal, and an automatic coffee dispensing machine. At supermarkets and other large properties the position could have been even worse. The number of hereditaments could have expanded massively, and the resource needed to maintain rating lists likewise. The Supreme Court’s decision is a welcome reminder that non-domestic rates are a tax on real property, and not a tax on business.

The task now begins to remove from rating lists many thousands of hereditaments erroneously created by the Valuation Office Agency, with retrospective effect. This enormous exercise does beg the question as to whether there should be a better way of dealing with such disputes. The Valuation Office Agency created more than 10,000 ATM site hereditaments at retail properties and did this with retrospective effect back to 2010. Rates have been paid on all those sites for ten years. These assessments will now have to be deleted from rating lists throughout England and Wales and the rates refunded to the ratepayers. Perhaps it would be better that such changes should be made only at the time of a general revaluation, or that there should be some limit on the ability to create “new” hereditaments retrospectively, so as to make the system better for ratepayers, for billing authorities and for the Valuation Office?